|

|

Vernichtungskrieg: Wehrmacht Complicity in the Holocaust on the Eastern Front

by Stephen Vargas(Stephen Vargas is a volunteer at the Holocaust History Project. He received his B.A. in History from the University of Notre Dame in 2010 and is currently seeking an M.A. in History from the University of Texas at San Antonio. His next project is an essay exploring the foundation, organization, and functions of the Hitler Youth from Weimar to the Third Reich).

Introduction

![]()

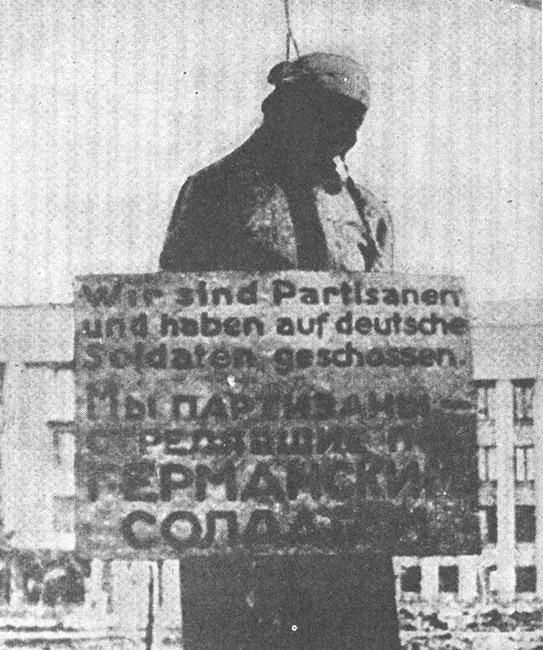

![]() Figure 1 "We are partisans, and have shot at German soldiers." The brutal war against civilian "Partisans"” was a marked characteristic of war on the Eastern Front.

Figure 1 "We are partisans, and have shot at German soldiers." The brutal war against civilian "Partisans"” was a marked characteristic of war on the Eastern Front.

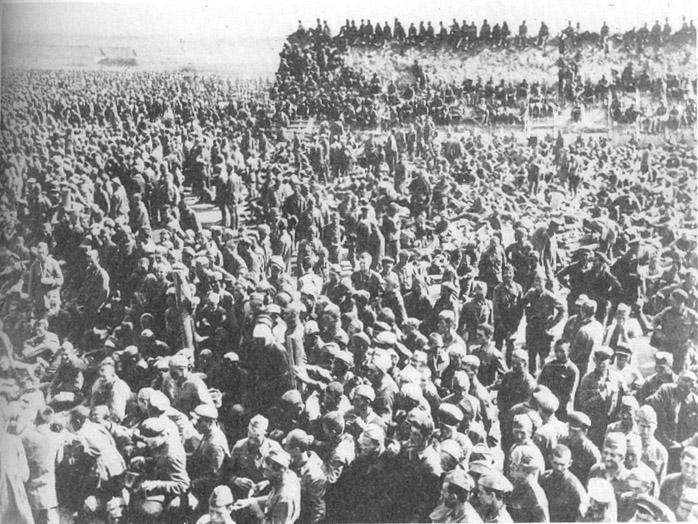

Contemporary curriculum on the Holocaust likely designates the passage of the Nuremburg Laws, concentration camps like Auschwitz and Dachau, and the SS and Einsatzgruppen as some of the more central points of study. Seldom do events like Babi Yar and the Partisan War in the East receive their due attention. The genocide of over 33,000 Jews in the span of two days at Babi Yar was, and has since been, unmatched with regards to its sheer scale. Moreover, the Partisan War resulted in unmitigated terror against civilian and military populations in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, a crucial characteristic of the war in the east. These are but a few of many examples of a Holocaust that occurred not in concentration camps, but instead on the battlefront where there was no true designation between civilian and combatant, Slav and Jew, and Communist and anticommunist. It is here that Hitler’s Kulturkampf (cultural war) burgeoned into a Vernichtungskrieg (war of annihilation) to rid of these aforementioned enemies of the Volk – who had curiously become melded into one euphemistic term permitting their liquidation: Partisan.

Beginning with the invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, Germany embarked on what would become arguably the most murderous, indiscriminate campaign in modern military history. Traditional historiography of German war efforts in World War II paints an image of unmitigated cruelty by such paramilitary forces as the Einsatzgruppen, the Waffen SS, the German Order Police, and radical auxiliary police units from the occupied territories. Indeed, the 1990 edition of the Encyclopedia of the Holocaust contains an entry on the Wehrmacht which makes no mention of crimes committed by the Wehrmacht, but instead complicit only through cognizance.1 However an emerging historiography has taken flight, especially after 1995 when an exhibition entitled "Vernichtungskrieg: Verbrechen der Wehrmacht, 1941-1944" began touring Germany and Austria. Translated to "War of Annihilation: Crimes of the Wehrmacht," the exhibit portrays essays accompanied by scores of photos that expose the Wehrmacht as yet another weapon of violent persecution in Hitler’s arsenal. While this emerging historiography had circulated among scholars for several years prior, its unbridled challenge of existing public thought proved to be quite controversial. Its authors, the Hamburg Institute for Social Research, brought into light a subject that had heretofore been considered settled, debunking the myth that the German Wehrmacht was an independent military apparatus who fought valiantly while maintaining its distance from Holocaust-related crimes. Why it took such a candid exposé as long as it did to be revealed to the public is reserved for further studies; however it can be surmised that prior to Germany's unification in 1990, such discretion was necessary. Politically speaking, the consequences of publishing a historical account of the Wehrmacht's complicity in the Final Solution by German historians could be devastating, especially given that many of the German Democratic Republic's founders were former members of the Wehrmacht – a potential coup de grace in a tense Cold War.2

In light of the intensifying discourse on this matter, this essay seeks to explain the extent of the Wehrmacht's complicity in Holocaust-related crimes during World War II. Its geographical range covers, in a general temporal succession, Poland, Lithuania, the Baltic states, Greece, and the Soviet Union. In terms of its victimized populace, although the Holocaust affected many types of minority populations, scholarly evidence elucidates the most persecuted individuals on the battlefront to be gypsies, Communists, Slavs, Jews, and Partisans – however as it was previously explained, by the early 1940s the distinction between these groups had become incredibly muddled under the guise of Partisanship. By the end of the war, the Wehrmacht had assisted, both actively or passively, in the murder of millions of minorities – resulting in one of the most murderous campaigns ever.

Although this essay aims to provide a comprehensive survey of an assemblage of various published scholarship on the topic – including justifications of actions, politicization of the army, indoctrination of the Wehrmacht, and region-specific manifestations of the Holocaust as perpetrated by the Wehrmacht – it is unrealistic to expect every individual argument within each subtopic to be explored. Instead, this is a broad overview of various scholars’ different, but fundamentally similar, interpretations of the Wehrmacht's role in the perpetration of the Holocaust during their Eastern campaign.

![]()

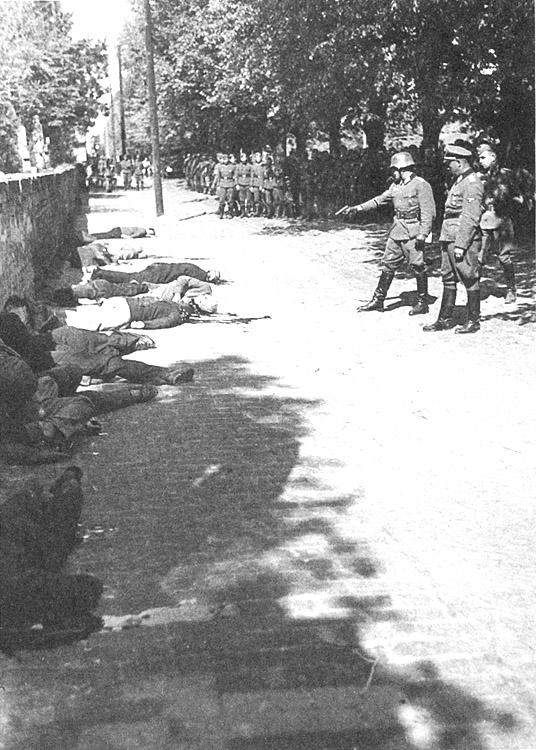

![]() Figure 2 This image of two Wehrmacht officers observing the burial of executed victims in Šabac renders the Wehrmacht cognizant, at best, of criminal actions in the East.

Figure 2 This image of two Wehrmacht officers observing the burial of executed victims in Šabac renders the Wehrmacht cognizant, at best, of criminal actions in the East.

Finally, it is worth noting that finding pertinent books in English for the composition of this essay was somewhat frustrating. Literature on the Wehrmacht in the Eastern front is ample; however, many scholars neglect the true nature of the war fought here, only focusing on the military history. Two particular books I came across were written by Werner Haupt, an officer in the northern sector of the Eastern front: Army Group South: The Wehrmacht in Russia, 1941-1945 and Army Group Center: The Wehrmacht in Russia, 1941-1945. Given their subject, I assumed that they would detail numerous occasions of Wehrmacht crimes in the Soviet Union; however Haupt conspicuously excluded any acknowledgement of the criminal nature of war there. Even if his intent was to provide a strictly military history, it is difficult to ignore that the Wehrmacht was engaged in, for example, a declared war against civilian Partisans – many of whom were certainly not Partisans. One can only assume that Haupt’s connection to that front dissuaded him from discussing the criminal nature of warfare there. Thus, Hannes Heer, whose scholarship on this topic is quite extensive, provided one of the best assumptions on the matter of writing such a history. Heer maintains that "To speak of crimes of the Wehrmacht thus means a decision to stop writing military history, and to start writing a social history of war."3 As such, a considerable amount of this essay is dedicated to discussing the social components of this topic – psychology of indoctrination, philosophy of duty, and life in the Third Reich as a civilian and soldier. The latter half of the essay, therefore, will focus on the military engagements which constituted a Holocaust on the Eastern front.

Explaining Complicity

A fundamental question that necessitates explanation in this essay is why seemingly ordinary Germans were compelled to either engage in or passively comply with genocidal acts. Many prominent historians have grappled with this query, including Christopher Browning, Omer Bartov, Daniel Goldhagen, Ulrich Herbert, and Hannes Heer, to name a few. However the overarching theme that permeates their studies is a general understanding that no such universal or definitive explanation exists. Delving into the minds of soldiers to explain how Nazi ideology became almost imbued in the cultural fabric of the average German is a seemingly impossible task, especially given that many of those living soldiers have since suppressed any semblance of cognizance or complicity, lest they shame their hitherto valiant efforts on the Eastern front. Thus, historians are forced to rely on more pragmatic historical and often times philosophical explanations. The former explanations are somewhat more reliable given their empirical foundations; however they do carry over into the philosophical realm as officers and soldiers would ultimately justify genocidal actions utilizing philosophical principles of duty. Before exploring these, however, it is important that I provide a disclaimer: justifications for committing war crimes are to be presented at face value; that is, I am not seeking to provide a case for their validity, but only wish to offer some of the arguments that have been presented post hoc (both by historians and the participants alike). It is thus up to the individual reader to discern for themselves whether these arguments hold.

Historical Roots

First to be examined, thus, are the historical roots of anti-Jewish/Bolshevism and radical National-Socialism among the average German [It is important to note here that the term "average" refers to those Germans that were conscripted into the Wehrmacht – this distinction is necessary because it differentiates them from members of the SS and SA, who were active members of the Nazi Party early on, as well as were fully aware of their task before entering the war.] preceding World War II. Aristotle Kallis, in his book Nazi Propaganda and the Second World War, argues that National-Socialism promoted an irredentist rebirth of the Volk. Accordingly, it was endorsed "in ethnic and territorial terms (union of all Germans – Gesamtdeutschland), geopolitical (putting an end to the crippling 'encirclement' of the Reich), racial (establishing a rigid hierarchy of value within German and in the rest of Europe), and 'missionary' (fulfilling its destiny vis-à-vis the Volk, Europe and the whole world)."4 Two key preexisting notions had to exist in order for National-Socialism to truly root itself in German society: anti-Semitism (of any kind), and a Weltanschauung (world view – although this is a fairly vague term) that was congruent with the Nazi understanding. Such sentiments were already in place, albeit on a smaller, more subconscious level. In order to understand the concept of Weltanschauung, the preexistence of anti-Semitism need be explained first, as it abetted in the formation of a formidable "other," with which the general population could ascribe its problems on and justify the need to save the Volksdeutsche (German people).

Anti-Semitism, in its most basic form, was historically rampant in Germany. Although radical anti-Semitism (manifested in the form of pogroms or other physical forms of violence against Jews) was not very prevalent, Ulrich Herbert deems "passive anti-Semitism" as having spread virulently during the years of the Second Reich and the Weimar Republic.5 This is because, as Daniel Goldhagen asserts, the Jews in German eyes' would always be a Fremdkörper, an alien body in Germany.6 Herbert believes that passive anti-Semitism, although lacking in its aggressive fanaticism, was more voyeuristic, simply alleging Jews of heinous crimes. In other words, "this brand of anti-Semitism was reactive rather than proactive."7 That being said, it was nevertheless prepared to accept radical programs, particularly when it came in the form of legal discrimination in 1933. Its legalization, thus, bred a sense of confirmation of these passively anti-Semitic views among its believers, since "no one who was so punished could possibly be completely innocent."8

Although these sentiments were historically characteristic of German society, the most direct and topical cause of their propagation was the results of World War I. World War I mired the German economy and the spirit of its defeated population. A decimated economy led to widespread poverty during the Weimar years, an obvious cesspool for popular dissent. Moreover, the stipulations set forth in the Treaty of Versailles bludgeoned Germany, essentially designating them as chiefly culpable for the war’s existence. Indeed, Part VIII, Section I, Article 231 stated:

"The Allied & Associated Governments affirm and Germany accepts the responsibility of Germany and her allies for causing all the loss and damage to which the Allied & Associated Governments and their nationals have been subjected as a consequence of the war imposed upon them by the aggression of Germany and her allies."9

Under this article, Germany assumed full responsibility for the outbreak of the war. Along with this burden, Germany was also charged with paying reparations (a sum of roughly $150 billion by today’s figures), ceding significant tracts of territory, and capping their military force at 100,000 men.10 All of these reprimands were seen by Germans as draconian and disproportionally harsh. The succeeding years of severe economic strife further augmented these contemptuous feelings as Germans endured some of their worst financial years in the wake of a humiliating military defeat. The economy was marred by high unemployment, hyperinflation, and corruption, issues which Hitler promised to alleviate. Predictably, Germans were taken by his rhetoric of change – a condition which is perhaps highlighted best by the words of Inge Aicher-Scholl, sister of Sophie and Hans Scholl [Sophie and Hans Scholl were among the founders of the White Rose, an anti-Nazi student-led organization that sought to bring to light the Nazi genocide occurring in the East, as well as promoted the overthrow of Hitler. Upon their dissemination of a leaflet at the University of Munich, they were arrested, interrogated, and beheaded for crimes of treason.] who were killed by the Nazi state:

"Hitler, or so we heard, wanted to bring greatness, fortune and prosperity to this Fatherland. He wanted to see that everyone had work and bread, that every German become a free, happy and independent person. We thought that was wonderful, and we wanted to do everything we could to contribute."11Aicher-Scholl’s statement highlights that even those who would later vehemently oppose Hitler’s leadership, ultimately suffering greatly for it, could not deny their optimism upon the advent of the Führer. Although certainly not universally felt in Germany, her sentiments are nonetheless quite telling.

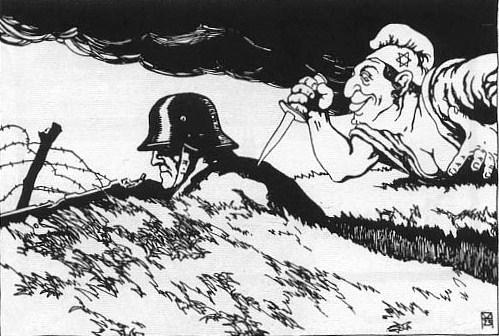

Yet those circumstances alone do not explain the continued growth of anti-Semitism/Bolshevism in Germany that made Hitler’s war in the East possible. It took a concerted effort of escapism by the military command and a receptive German population following WWI, which was manifested in the "stab in the back" myth. In order to exonerate the military of any culpability for Germany’s defeat, a myth was created which suggested sabotage on the homefront: both by the general public in failing to fulfill their end of total war, and by Jews, Bolsheviks and other Communists who surreptitiously undercut the war – including those Jews who fought on the battlefield and came to be known as "cowards, deserters, and traitors."12 Not wanting to bear such a perfidious tag, Germans quickly shifted all the blame onto Jews and Communists. Henry Metelmann, who published his autobiographical account as a Wehrmacht soldier, recalled his time in Hitler Youth when "it was drummed into us" that "we had lost the war because the German workers, led, of course, by Communist agitators, had treacherously put the knife in his back by going on strike while [the soldier] held the front-line against the numerically superior enemies."13 [ It is important to note that Metelmann’s affiliation with the Wehrmacht may raise questions regarding his inclination towards perpetuating a self-exculpating myth; however there is a general historical consensus regarding the existence of this myth and the government’s purposeful diffusion of it to a generally responsive population. Thus, Metelmann’s account should be regarded in the sense that a myth existed and its targeted audience responded, for the most part, positively to its existence.] The creation of a Jewish-Bolshevik conspiracy is of little surprise, as Goldhagen asserts that Jews came to be seen as responsible for "everything that was awry in society, from social organization, to political movements, to economic troubles…"14

Explicating the Soldier’s Mind

![]()

![]() Figure 3 1919 cartoon depicting Jewish treachery on the homefront during WWI.

Figure 3 1919 cartoon depicting Jewish treachery on the homefront during WWI.

Unlike the civilian German, the German Soldat should be examined as a different species – particularly because of the Wehrmacht’s significant standing in Nazi Germany. By 1933, Hitler had placed an enormous emphasis on the Wehrmacht by declaring it the "second pillar" of the state, alongside the Nazi Party15 – the seeds for a political unification had been sewn almost immediately. This politicization of the military, which will be explored further in later paragraphs, enabled Hitler to exploit the soldier as his personal executioner. But why would a soldier submit to such a bastardization of warfare? German ambassador to Rome, Ulrich von Hassel poignantly noted in his diary in May 1941: "With this submission to Hitler’s orders, [OKH Commander-in-Chief Walther von] Brauchitsch has sacrificed the honor of the German Army."16

Indoctrination of ideology certainly played a seminal role in the Wehrmacht’s personal justifications; however the fundamental rationalization for their amoral engagements rested in their soldierly duty to serve the state. SS-Obersturmbannführer Adolf Eichmann, a principal perpetrator of Holocaust crimes, alluded to Kant’s principle of the categorical imperative during his hearing at the Nuremburg Trials. Simply put, a categorical imperative is an absolute universal and moral obligation or duty. Kant identifies the lone categorical imperative to be: "Act only on that maxim whereby thou canst at the same time will that it should become a universal law."17 Eichmann’s understanding of Kant was fundamentally distorted and selective, however, and he asserted that he "could include in this principle the concept of obedience to authority. This I must do, for this authority was then responsible for what happened." He goes on to explain, "Since the formulation of the Kantian principle, there was never so destructive an order from the head of a state as there was from the Nazi Führer. And so there was no precedent." In other words, Eichmann maintains that he followed Hitler as the moral legislator under this Kantian principle because the principle itself had heretofore never been challenged by such a figure. This enabled him, thus, to conclude that "I was only a small man receiving orders, and could not bear responsibility."18 Eichmann’s moral justification for duty was clearly a flawed interpretation of Kant, with almost certain escapist intentions; however it is significant chiefly because it touches on a seemingly universal justification among many rank and file war criminals across time and space – that being a sense of entitlement and imperviousness to moral standards, attributed fundamentally to the ruling body’s established standards and orders. The complicit Wehrmacht should be included among this group.

Such vague understandings of duty are lucidly demonstrated in accounts by Wehrmacht soldiers both during and after the war. For instance, Lt. Hubert Becker explained, "We didn’t understand the Russian campaign from the beginning, nobody did. But it was an order, and orders must be followed to the best of my ability as a soldier. I am an instrument of the State and I must do my duty."19 Henry Metelmann reiterated this point in the opening sentence of his autobiography: "Born into a working-class family, the conviction not to trust my own intelligence but to leave everything important to my 'betters' was a part of my way of thinking since early childhood."20 Metelmann uses this statement to elucidate his belief that he never thought he could write a published book, but its undertones suggest much more: justification for military subservience to one of the most notorious figures in history. This was expressed in Wehrmacht leadership, as well. Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, who initially objected to exclusionary laws against Jews in the military, swore by his now famous mantra in light of the murders of Jews and Hitler’s catastrophic failures on the battlefields that "Prussian field marshals do not mutiny."21 Hannes Heer examined the moralization of crime, concluding that Paul Tillich’s term "transmoral conscience," suited these soldiers best. This is because, "in their minds misdeeds figure as good deeds, and criminal behavior becomes the enactment of the moral code." Their behavior is therefore possible under specific conditions: "by conquering one’s ‘weaker self’ in favor of demands externally dictated ‘by the state or philosophy (Weltanschauung),’ by setting aside the wishes formed in one’s ‘private and personal life’ in favor of ‘the greater entity,’ in other words of the Wehrmacht, Germany, or simply ‘der Führer.'"22 Thus, an errant, rigid sense of duty to the state seemingly interned members of the Wehrmacht – this, of course, does not relieve them of their actions. Perhaps the best conceptualization of their role under these pretenses of duty, however, is André Mineau’s term “Mitäufer.” Translated by Mineau to "fellow travelers," he argues that it encompasses those who engaged in Nazi ventures because they either shared some (magnitude or severity are irrelevant here) similar goals with the Nazi’s, because of some form of professional subservience, or both.23 Given its emphasis on shared ideology of any degree, Mitläufer is an appropriate description of the Wehrmacht soldier prior to their radicalization and execution of war crimes, as will be elucidated later.

Indoctrinating the Wehrmacht

Given the historical explanations and philosophical justifications of their complicity, the Wehrmacht could be, and indeed was, viewed as a highly malleable military apparatus. Propaganda, as a consequence, was ceaselessly used to transform the German male into an obsequious soldier through any possible means. As one Wehrmacht soldier facetiously put it, "Whenever I see a man in uniform now, I picture him lying on his face waiting for permission to take his nose out of the mud."24 Yet the Wehrmacht’s obedience is no laughing matter. Complying with orders of a terroristic nature required much more than the standard rote indoctrination, although this certainly was a contributing factor. Instead, Hitler’s method of indoctrination was all-encompassing, in terms of both temporality and modality.

Training: Hitler Youth to the Wehrmacht

Indoctrination began early on in Nazi Germany, primarily with the regimentation of young boys in Hitler Youth. Hitler Youth is typically associated with the indoctrination of more radical members of the Nazi Party, but Henry Metelmann’s autobiography serves as an excellent paradigm for those numerous amounts of members who were eventually conscripted into the Wehrmacht. These members were not taken solely by the radical ideological current, but rather more simplistic, practical appeals. Metelmann found himself considerably enticed by Hitler Youth after his Christian scout group was taken over by it, asserting that "I thought the uniform was smashing… Where before we seldom had a decent football to play with, the Hitler Youth now provided us with decent sports equipment, and previously out-of-bounds gymnasiums, swimming pools and even stadiums were now open to us." He continues, "Never in my life had I been on a real holiday… Now under Hitler, for very little money I could go to lovely camps in the mountains, by the rivers or near the sea."25 While promotion of change enabled Hitler to garner support from the elder population as he attempted to consolidate his power in 1933, the crux of his ideological exertions would shift to the younger population; and as Metelmann demonstrates, Hitler achieved this by opening up a wealth of avenues to young German boys who had hitherto lived in a dispiriting Germany hampered by economic destitution. Moreover, Hitler Youth members were taught about the necessity of Lebensraum in the East, and the glory of fighting and dying for Fatherland. Metelmann recalls a strong sense of importance when the police stopped traffic as he and fellow Hitler Youth members marched down streets. These marches, unbeknownst to Metelmann at the time, would run through working class quarters to display Hitler’s authority to a crucial population. 26

When Metelmann and other young Germans were finally absorbed into the Wehrmacht, they experienced similar tactics of rote regimentation and indoctrination. Metelmann recalls, "Our officers and Sergeants made no secret of their aim to mentally and physically break us, in order to remake us in their image in the Prussian tradition," noting that the similar training in the Hitler Youth "meant the Army was able to train us more speedily."27 Other soldiers support this claim, arguing that the persistent physical and mental harassment in training was meant "to break us, to make us lose our will so we’d follow orders without asking…"28 Subsequent military parades as the war neared further incited sentiments of pride and significance. As an aggregate, these subtle methods of "military training" were ultimately intended to fashion a soldier from his earliest years, perhaps preparation for the ‘unsoldierly’ duties he would fulfill when Hitler finally pushed Germany into war. But to achieve this, simple repetitive regimentation would not suffice. It took a comprehensive plan in which the political realm would be united with the military.

Uniting politics and the military

Carl von Clausewitz, in On War, wrote of the political object’s influence on the military object: "War is an instrument of policy; it must necessarily bear its character, it must measure with its scale: the conduct of War, in its great features, is therefore policy itself, which takes up the sword in place of the pen, but does not on that account cease to think according to its own laws."29 Clausewitz, as a Prussian officer, was highly influential on German military thought, and Hitler was no exception. Save the last bit on military’s accordance with its own law as opposed to those offered by the "pen," this quote, above all else, may exemplify exactly why. Of chief strategic importance for Hitler’s plans was the creation of a military that was, first and foremost, a political ideologue. Previously mentioned was Hitler’s politicization of the army when he proclaimed it to be the "second pillar," only behind the Nazi party itself. Hans Fried argues that militarism is a marked characteristic of National-Socialism, concluding that the National-Socialist ideology was embedded in the fabric of German militarism.

"This militarism is characterized as much by the establishment of tyranny at home as by its treatment of conquered territories or allied countries. No technical distinction between the tasks assigned to the professional Army on the one hand, and to the Party or the government on the other, can obscure the fact that they have been working together to perfect a special type of militarism. To name it National Socialist Militarism, is not to say that it is merely militarism of the German National Socialist Workers’ Party. Rather, it means a militarism in which National Socialist methods and doctrines permeate the actions of all the protagonists. Whether or not all of them have been members of the Party, or any similar irrelevancy, does not alter the facts."30Fried demonstrates that there is no true distinction between military and political ideology. National-Socialism’s invasive nature enabled the latter to infect the former. As a result, it was ostensibly inevitable that Hitler would ultimately dictate the strategic, logistical, and moral frameworks of the Wehrmacht. Much like his discriminatory policies of the 1930s, Hitler obtained compliance by the military through legal means.

In 1934, Hitler appointed himself the Wehrmacht’s Supreme Commander, which Syzmon Datner identifies as "a fact that was bound to have an effect on the generals’ [of the Wehrmacht] way of thinking and the indoctrination of the German soldier…"31 On February 4, 1938, Hitler assumed direct command over the Wehrmacht when the Ministry of War was abolished and the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, or OKW, was created in its stead. The previously autonomous (at least in theory) Ministry of War lost its traditional function of war planning and military guidance as they became the purview of Hitler and his appointed OKW directors, then Generals Wilhelm Keitel and Alfred Jodl. [Keitel was later made Field-Marshal and Jodl became the Chief of Operations Staff. ]32 Soon after the creation of the OKW, Chief of Staff of the German General Staff Ludwig Beck, a more traditional Prussian General who resented Hitler’s encroachments on the Ministry of War, resigned from his post. Moreover, by December 1941, Gen. Walther von Brauchitsch was relieved and Hitler assumed the official post as Commander in Chief of the Army. Although Brauchitsch certainly did not provide any opposition to Hitler while commanding, his removal and Beck’s resignation "removed the last vestiges of the General Staff from the planning and military advisor process."33 The Wehrmacht was wholly Hitler’s army. Of considerable importance to this discussion is an assessment offered by Richard Carnicky on Hitler’s ability to efficiently ensnare the Wehrmacht as his war lackey: "Since the German General Staff placed greater importance on technical proficiency and removed the soldier from the political decision making process, the army’s leadership was inadequately prepared to counter Hitler’s radical views on war."34 Thus, they believed that foreign policy decisions would remain under their authority, as it traditionally had. Of course, Hitler would essentially blitz them when he took office, and recognizing that legal stratifications alone would not suffice, Hitler employed radical rhetoric to decisively capture the Wehrmacht.

Hitler’s emphatic oratory delineates him from most leaders, and it is unsurprising that he utilized rhetoric to its full capacity when attempting to achieve conformity. Michael Florinksy’s 1936 book, Fascism and National Socialism, is an excellent source for examining this. A scholar of Russian Bolshevism, Florinsky decided to dabble in the study of Fascism and National Socialism in 1936, assembling his knowledge through two visits to Nazi Germany in 1934 and 1935. Having conducted street interviews with German citizens, including both Nazi and non-Nazi party members, Florinsky’s book is significant for three reasons: its explication of German receptiveness to the Nazi party, a topical account of life in Nazi Germany during its crucial pre-war years, and a prognostic examination of the state’s direction in coming years. He uses Hitler’s assertion that "The individual is nothing – das Volk is everything!” to demonstrate the supremacy of the state.35 Under this assumption of the individual’s absolute subservience to the state, Florinsky believes that Fascism and National Socialism’s “glorification of the State and the Nation leads them along the path of extreme militarism."36 Moreover, "Their ideology… is the bread of… 64 million Germans, and it is being disseminated with an energy and persistency that no other government, except that of Soviet Russia, has ever displayed before…"37 Florinsky’s opinions presaged precisely how history would play out. He further attempted to explain this prospective future and the seeming inevitably of war by noting that Fascism and National Socialism view war as “the supreme test of the Nation but also the most sublime of experiences for the individual.” He continues, "National Socialist leaders have repeated over and over again that war is for the man what child-birth is for the woman."38 Such extreme rhetoric intricately bound party policies and aims with those of the now-established, subservient military. Thus, by the time the war began in 1939, Wehrmacht commanders “concurred ‘that in future greater importance should be attached to instruction on the National Socialist worldview and national policy goals.’”39 National-Socialist rhetoric, however, had already been disseminated en masse through comprehensive propaganda.

Exploiting preexisting societal values

Several scholars, including Bartov and Kallis, argue that Nazi Weltanschauung was most effectively implanted when it harped on existing and established emotions, aspirations or values.40 41 Hans Fried supports this hypothesis, arguing that "a nihilistic movement of such destructive power [like that of the Wehrmacht’s barbaric campaign in the East] cannot base itself on cynics" but instead on such things as "misguided idealism..."42 In other words, propaganda was so efficiently disseminated in Nazi Germany because many of the prejudices and values requisite for Nazi policies were already embedded, at least to some extent, in the minds of the recipient population. "Successful propaganda," Kallis argues, "does not always tell its audience what they most want to hear; it also seeks to maximize the appeal of an otherwise unpopular decision by linking it with established aspirations… of the public."43 In order to persuade Germans of their discriminate policies, the Nazis needed to establish and integrate ‘long-term emplotment,’ [Coined by Hayden White in his 1973 book, Metahistory: The Historical Imagination of Nineteenth-Century Europe, "emplotment" is the construction of a narrative with a plot using a series of historical events.] in which they coherently linked past, present and future events, and ‘short-term justification,’ in which they provided a temporary rationalization of their policies. When successfully integrated, these two categories work concurrently to legitimate a suspect short-term policy with its effectuation of a long-term goal that is not simply putative and unnecessary, but rather concretely rooted in a historical imperativeness.44

An example of this would be the consensus amongst German public opinion when it came to dismantling the Treaty of Versailles. The regime’s step by step rescission of the treaty’s restrictive clauses facilitated the ease of garnering support.45 Anti-Semitism, moreover, was long entrenched in German public opinion, especially given that the Nazi’s conceptual contribution to anti-Semitism was so rudimentary, focusing on a simplistic mono-causal interpretation of past debilitating circumstances (as mentioned prior): the Bolshevik revolution, German defeat in WWI, the "stab in the back" myth, the 1918 revolution in Germany, stipulations of the Versailles Treaty, the Weimar Republic, and the 1929 economic crisis – all of which emanated from the Jew’s Weltverschwörung (international conspiracy).46 Resultantly, civil service and military exclusionary laws in 1933/34 and the Nuremberg Laws in 1935 faced relatively unobstructed passage. Again, the Nazis achieved these policies because they could rely on preexistent notions of similar taste – thus, revolutionary tactics would not be needed.

Putting it all together: preparations for war

The story of the soldier differed. Paramount to understanding their motivation to wage a criminal campaign is their notion of the enemy as, indeed, an Untermensch, or subhuman. This transformation occurred because the Nazi Party was able to endorse a moral reification of the enemy. Discussed by André Mineau, he argues that soldiers understood and tolerated the denial of human dignity to its enemies because of a subconscious moral reification that had occurred within their individual moral frameworks. What this means is that a moral mental process existed in which certain beings were designated "below the level of ontological value required for reciprocal morality."47 Consequently, "higher beings" are permitted to dispose of them. Mineau believes that this notion of a morally reified enemy applied to any Slav, Jew or occupant of conquered Lebensraum – needless to say, it was quite comprehensive.48 Assisting the diffusion of this amoral "moral" permission, members of the Wehrmacht were able to rest on their a posteriori justifications.

In the East, the Wehrmacht was to fight on a geographically harsh front against an enemy they had historically perceived as backwards and brute. Nazi high command recognized this, and given this distinctive circumstance, Goebbels did not endeavor to provide strict literary propaganda for servicemen because "the soldier ‘lives’ the Weltanschauung at the front."49 Logically, the most efficacious mode of indoctrination would be on a plane in which the German soldier was out of his element, stacked against a mythicized enemy and its equally savage populace – thus, the conceptualization of the Untermenschen met its physical form. Many soldiers’ only knowledge of the East was the lingering memories of their hapless fathers who faced a nefarious enemy during the First World War.50

Consequently, a disdainful concept of the "East" as backward, uncivilized, and uncultured developed, with Jews assuming the role of aggregate enemy. Indeed, one Wehrmacht private, upon invasion of Poland, believed that "the time had arrived for the ‘National Socialist people’s army… to march against ‘Juda’ the world-enemy."51 Another conscript relayed to his parents prior to the invasion of Russia, "While eating dinner the subject of the Jews came up. To my astonishment everyone agreed that Jews must disappear from the earth."52 Examples of anti-Semitic thought are rampant – one private involved in the invasion of Poland claimed

"[In Poland] one can see these beasts [Jews] in human form. In their beards and caftans, with their devilish features, they make a dreadful impression on us. Anyone who was not a radical opponent of the Jews must become one here. In comparison to the Polish caftan-Jews, our own Jewish bloodsuckers [in Germany] are lambs. No wonder that after [only] twenty years the Polish State has become victim to these parasites…. We recognize here the need for a radical solution to the Jewish question."53Thus, the radicalization of previously passive anti-Semitism occurred as soldiers were exposed to foreign fronts. This would be augmented with the orders of unbridled warfare that would ensue, thereby hardening the soldier. Hannes Heer’s argument that it was the Reich leadership’s intent to radicalize the army through mass killings of Slavs and Jews in the East supports this assertion.54

The Nazi party’s avid promotion of the Untermenschen clearly permeated the Wehrmacht soldier’s mind. As Mitläufers, a term previously discussed, soldiers possessed precisely enough of a contemptuous conceptualization of their Eastern enemy that their experiences on the battlefield, coupled with their onus of duty, would suffice to enable Hitler’s Vernichtungskrieg to be carried out. As a pseudo-legal basis for their impending crimes, the Nazis stressed that because the Soviet Union was not present at the 1929 Geneva Convention this permitted a circumvention of international law, particularly with regards to the ethical treatment of POWs.55 Not surprisingly, this suspect legal justification became increasingly murky, permitting a wider array of crimes as the war waged on. Not to be discussed now, but certainly a set of orders which benefitted from this witting misinterpretation of international law, are the Barbarossa Orders, established from Operation Barbarossa’s inception until its disbandment.

Compliance was achieved because the High Command and officer corps’ minor ideological congruencies enabled the Nazis’ war to become a reality.56 Field Marshal Walther von Brauchitsch’s belief that no other institution or group was, or should be, more affirmative of Nazi ideology than the officer corps typifies the importance of an obedient military leadership.57 These well-educated officers (overtly exposed to the Nazi ideologies over the course of their studies) exercised a rigid regimentation of their less educated, but obedient rank and file. Thus, they constantly reminded their troops that the German soldier draws his psychological strength from the "ewigen soldatischen und ethischen Werten der Nation (eternal soldierly and ethical values of the nation."58 By establishing these moral guides, they prepared the Wehrmacht for a war that was not to be waged against another army, but against another people. They were cognizant of the fact that the untraditional type of war they would engage in would bear a heavy psychological effect on the soldiers, because as Jan Philipp Reemtsma asserts, "once war is construed not as a struggle between armies but between peoples, then the war is over only when the enemy people as a people has been annihilated or at least rendered defenseless."59 Thus, when the war on the eastern front finally broke out, the Wehrmacht was prepared to assume its prescribed role as "arms bearer" of the Nazi regime – a position that would come at an astounding cost to its enemy population.

Crimes Committed by the Wehrmacht

In November 1939, as a response to objections about the SS’s brutality, Hitler curtly retorted, "One can’t fight a war with Salvation Army methods."60 This facetious comment by the Führer exemplified Hitler’s perception of how the war should be conducted in the East – devoid of empathy and emphasizing deserved punitive measures against the invaded territory. Although Hitler’s agenda for war in the East was clearly calculated on ideological grounds prior to the invasions, the precise logistics of its conduction were not. Thus, as the coming sections will elucidate, the crimes committed by the Wehrmacht evolved over time as the leadership adapted methods for conducting their Vernichtungskrieg on a region-specific basis – both for efficiency and deniability, as a loss came to appear inevitable. The first case will be Poland, where extermination policies were tested; then I will examine Greece and the Balkan states of Yugoslavia where the aggressive tactics against Partisans became legitimized; and finally I will look at the Soviet Union, the location of perhaps the most heinous crimes committed during the war’s entirety.

As a brief note: the Wehrmacht is comprised by multiple forces, including the Heer (army), the Luftwaffe (air force), and the Kriegsmarine (navy). For the sake of brevity, only the Heer’s crimes will be examined; particularly since the Kriegsmarine was based away from the Eastern front, and the extent of the Luftwaffe’s crimes were advanced sorties that targeted pockets of so-called "Partisans." Thus, their removal from the field eliminated the personal nature of committing such crimes, obliging less indoctrination by command.

Poland: Assessing the Wehrmacht’s Receptiveness

On the very day that the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was signed, Hitler addressed his Wehrmacht generals at the Berghof on his expectations for the impending war in Poland, a segment of it which was documented in Helmuth Greiner’s diary:

"Politically there had been a remarkable achievement, now the Wehrmacht would have to prove itself and demonstrate its ability. The war would be waged with the greatest brutality and ruthlessness and until Poland was totally destroyed. The goal was not to occupy the land but to annihilate all forces. He would create the reason for the war. Later in history no one would ask about the reasons."61Thus, Hitler’s plan for Poland was deliberate, lacking only a public impetus for engagement. On the eve of the invasion of Poland, Hitler made that contrived impetus explicitly known during a radio address to Wehrmacht troops:

"The Polish State has rebuffed my attempts to negotiate peaceful, neighborly relations; it has instead resorted to arms. Germans in Poland are being persecuted with bloody terror and driven from home and farmstead… I have been left with no other choice than to use force against force… Always remain aware in every circumstance that you are representatives of Greater National Socialist Germany! Long live our people and our Reich!" 62This poignant appeal on the grounds of overt Polish provocation emboldened Wehrmacht soldiers who, as discussed earlier, were already predisposed to harp on anti-Semitic/Slavic prejudices when they conducted war and occupation. Consequently, in Poland we find the incipient cases of war crimes by the Wehrmacht. Following their invasion and swift victories, members of the Wehrmacht were exposed to the initial phases of Hitler’s Holocaust in an attempt to accustom them to the new expectations of how war should be waged in the East. Thus, the hope was that the Wehrmacht, who led the invasion of towns, would gradually adopt into their toolkit the racial acumen possessed by the SS groups, who followed closely behind them clearing the towns of Untermenschen. Although "official" policies stressed absolute separation of duties between these groups, its practical application, as we will see, was quite the opposite. What would come to characterize the Wehrmacht’s complicity in Poland was passive compliance through unopposing observation of public murders, war crimes against POWs, and in many instances, direct involvement in shootings of civilians or unarmed army personnel – however the uniting factor of all of these was a general sense of apathy towards the ethical treatment of the Polish population, obviously spurred on by racial and ethnic prejudices.

When the army invaded Poland, they came upon an army and people that had been mythologized in their minds as indeed subhuman. Examining the Erfahrungsberichte (field reports) of the invaders, Alexander Rossino notes that derogatory comments about the Polish landscape and people peppered these reports. POWs were described by one soldier as behaving "entirely un-European, even inhumanly"; another described the civilians as "Polish swine" and "damned civilian swine;" and some towns were viewed as "knuckle deep in squalor."63 Such commentaries were endemic in the field reports of Wehrmacht soldiers, elucidating their perception of the subhuman Pole and Jew. Accordingly, Mineau’s suggested reification of the enemy comes into play here, as soldiers wrongly justified mistreatment of the occupied populations because they were unworthy of ethical treatment. This would ultimately come to be partially remedied when command began taking disciplinary action against Wehrmacht crimes, however they did not curb them entirely.

Crimes Against Unarmed Civilians

The Wehrmacht’s treatment of unarmed civilian Poles ranged anywhere from plundering, to rapes, to outright murder. A report dated just 16 days after the invasion highlights an incident in which a Polish girl just 16 years old was forcibly raped by two soldiers in her parents’ bedroom.64 In another case, three soldiers broke into a house late at night and pistol-whipped members of the family in their beds. They then proceeded to rape the 20-year-old daughter at gunpoint in front of her family, eventually leaving with several of their material possessions.65 In the latter case, the soldiers were reported as having been arrested by field officers, but the unruliness of Wehrmacht soldiers in instances of rape was rampant in field reports.

Crimes extended beyond rape and looting, however, as there were numerous cases of soldiers murdering Poles and Jews with either no provocation, or as retaliatory measure against contrived enemies. An example of a case in which no provocation was compulsory for execution is the murder of about 900 Jews on September 15, 1939 after Przemysl was taken by the Wehrmacht. The bodies were tossed into mass graves, which were later exhumed and concealed in 1944. The reason for this crime was "Jewish origin."66 In this instance, outright anti-Semitism prompted this massacre.

Other cases arose from retaliatory efforts by members of the Wehrmacht. In one case, members of the 8th Air Reconnaissance Unit found four mutilated German soldiers in the town of Konskie. Enraged, they gathered an undetermined number of Jewish men and forced them to dig their own graves at the local graveyard, all the while kicking and beating them. The local commander, Major Schulz, confronted the soldiers after watching the scene for some time, and told them that although Jews were the "source of all misfortune in the world," the troops still had to demonstrate discipline. The soldiers agreed and began to disperse, however other soldiers who had gathered to watch the initial scene, then proceeded to beat the Jews again as they attempted to flee. One soldier fired a shot, prompting others to fire. The result: twenty-two Jews dead. The soldier who fired the initial shots was court martialed, but only received a one year sentence because the court ruled his actions partially rational given his discovery of the mutilated bodies.67 Another massacre of 200 unarmed civilians occurred when the 95th Infantry Regiment with an attached SS group entered the town of Zloczew on September 3, 1939. Germans stopped one Pole as they marched in, inquiring whether Polish forces or Jews were in the town. There were then reports of random firing by soldiers into houses, despite an absence of resistance. That night, as another Polish witness recalled, Wehrmacht personnel "ran amok" as they fired on refugees in the town. Victims included a ten-year-old girl disemboweled after being shot in the back and a one-and-a-half-year-old girl whose skull was crushed by the butt of a soldier’s rifle. Postwar investigations concluded that it was highly unlikely that the massacre of civilians in Zloczew was accidentally committed during the heat of battle, as the miniscule remnant forces left behind to defend the town were deemed by the invading company to be sporadic and uncoordinated. Nevertheless, the accused members of the Wehrmacht maintained that they did encounter pockets of civilian resistance prompting their response.68 Thus, such retributive measures often provided impetus for murdering unarmed civilians and Jews in Poland, regardless of the enemy’s existence.

Crimes Against “Guerillas”

These punitive actions eventually came to take on a more systematic nature, as an informal tit-for-tat policy took hold among companies. Deeming the civilian population to be "guerilla" or "Partisan" ensured that swift and decisive measures could be taken against perceived enemies of the Wehrmacht. In other words, they could simultaneously massacre civilians and avoid martial reprimand by simply deeming them "Partisans." What is important to note is that even when civilians were defending their towns, arguably a form of "Partisanship," the brutality exhibited by the Wehrmacht was especially harsh. One such example is the XIII Corps’ eastward advance through Poland in the first two weeks of the invasion. Passing through the town of Ostrówek one night after the company suffered seven casualties in a town eight miles to the west, troops of one division began randomly burning homes and machine-gunning civilians. One victim, Aniela Hes, recalled her 77-year-old father being shot as he attempted to flee, her brother-in-law being shot while looking out his window, and her sister being killed when she opened the door to see what has happening. The commanding General maintained that the company had been fired on by the civilians, and evidence does show that they did experience some sniper fire earlier in the day. Ultimately, however, the troops’ response was vengeful and disproportionate given the limited resistance they experienced.

![]()

![]() Figure 4 Soldier posing next to executed Polish civilians in Ciepielów.

Figure 4 Soldier posing next to executed Polish civilians in Ciepielów.

POWs were sometimes adorned with the undesirable tag of "Partisan" as well. A soldier of a motorized infantry regiment reported, for example, on the massacre of 300 Polish prisoners after 14 members of their regiment were killed. He reports, the commanding Colonel Wessel "asserts that these [responsible] snipers were Partisans, even though every one of the 300 Poles taken prisoner is wearing a uniform. They are forced to take off their jackets. There, now they look more like Partisans." The "Partisans" were then marched to a ditch where the soldier found them all shot. He then states, "I risk taking two photographs, then one of the armed motorcyclists who did the job on orders from Lieutenant Colonel Wessel posed proudly in front of my lens."69

The blatant malevolence exhibited by these soldiers for the Polish people was staggering. By labeling their enemy’s population "Partisan," they were able to (in their minds) circumvent international laws, all the while relieving themselves of any remorse – as seen in the soldier who proudly stood next to his prized kills. Acts of retribution against Partisans was no extant phenomenon, however. In Poland it was somewhat of an informal system that still received some criticism from military courts, but later in the war it would truly become a systematized mode of exterminating undesirable populations, popularly supported by the Wehrmacht’s leadership.

Crimes Against POWs

As evinced by the aforementioned incident, Polish POWs received horrific treatment once in the hands of the Wehrmacht. The question of the treatment of POWs in all areas occupied by Germany was deliberated at the Nuremburg trials from 1945-1946. Their finding was:

"Prisoners of war were ill-treated and tortured and murdered, not only in defiance of the well-established rules of international law, but in complete disregard of the elementary dictates of humanity"70This mistreatment began from the outset when Germany invaded Poland, and reports certainly support the trial’s assertion.

On September 12, 1939, prisoners were moved into a local elementary school building in Szczucin, among them wounded soldiers. After a Polish officer seized a Wehrmacht officer’s pistol and shot himself and the German, grenades were instantaneously thrown into the building and soldiers outside began to open fire. Members of the Wehrmacht battalion then set fire to the building, and according to the testimony of two Polish priests, "Some [Polish] soldiers tried to jump from the upper story and the roof of the building, but the Germans shot at them and killed them on the spot."71 Seven days later on September 18, 1939, soldiers from an unidentified Panzer unit entered the village of Sladów where they "shot and drowned over 300 people, including some 150 war prisoners…"72 Szymon Datner contends that further offenses were committed by the Wehrmacht during their September 1939 campaign, "including cases of maltreatment, or even murder, of wounded prisoners, and the murder of medical personnel, in disregard of the Red Cross emblem."73 This would set a precedent for the eventual treatment of prisoners when Germany invaded the Soviet Union.

Establishing the Wehrmacht’s Role

The result of the apparent apathy towards the ethical treatment of Poles and Jews during Wehrmacht’s invasion and occupation created a highly undesirable situation for Poland’s population. The ideological currents promoted by Hitler and the high command endorsed a racially driven war, yet astonishingly the Wehrmacht’s high command was somehow taken by surprise when its soldiers began engaging in discriminate killings of civilians and POWs. A marked trait of Poland, thus, was recalcitrance by the Wehrmacht rank and file resulting from technical and authoritative disorganization within the Wehrmacht. This is seen in complaints by senior officials in the Wehrmacht, whose reasons for lodging complaints against their soldiers’ exposure to war crimes (whether it was those they were directly involved in or those that the SS committed in front of them) ranged anywhere from moral repugnance to a loss of military discipline to a jealous defense of the Wehrmacht’s executive authority on the Front.74 Gen. Johannes Blaskowitz claimed that "the troops do not want to be identified with the atrocities committed by the Security Police, and refuse any cooperation with these Einsatzgruppen…,"75 while Gen. von Brauchitsch complained of a Police Battalion’s exclusion of Wehrmacht assistance in a "military" operation.76 Opinions of disapproval of SS operations on moral grounds like Blaskowitz’s did exist, however not in great numbers in terms of formal complaints. Conversely, many objections resembled those of Brauchitsch who felt the SS operations were encroaching on the Wehrmacht’s authority. The most complaints, however, came from officers that were concerned by the potential of soldiers becoming unruly and losing their military discipline. Thus, they would issue orders like Commanding General of the XVIIIth Army Corps Georg von Küchler did in July 1940:

"… I emphasize the necessity to see to it that all soldiers of the army, especially officers, refrain from any and all criticism of the battle with the population of the GG [General Government], for example the treatment of Polish minorities, of Jews, and of church affairs… Certain units of the party and of the state are entrusted with carrying out this völklische struggle in the East. Soldiers are to keep their distance from these affairs of others units."77As this order demonstrates, eventually the Wehrmacht leadership was able to organize their understandings of the necessary rapport between them and the SS groups – that being a strict demarcation between the Wehrmacht soldier’s duties and those of the SS. While this still did not do much to curb the frequency of Wehrmacht involvement in crimes, their role as an ideology-driven force was radically altered when Germany rescinded their non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union. The complexity of this relationship changed as they began to work side-by-side, with racial eliminationist policies now emanating from the Wehrmacht high command’s orders, thereby suggesting them permissible by the average soldier’s ethical and soldierly code.

Greece and Yugoslavia: Anti-Partisan Wars and Reprisal Killings

In 1941, in preparation for Germany’s imminent invasion of the Soviet Union, Hitler aimed to secure his southeastern flank by invading Greece and Yugoslavia. The offensive began on April 6 with the assistance of Italian forces, and Yugoslavia and Greece both capitulated on April 18 and April 21, respectively. While Greece would remain intact as a state, divided among its victors into multiple zones of occupation, Yugoslavia was completely dismantled with individual regions divvied out to the various Axis partners.78 Similarities did exist between these two states, beyond their swift capitulation to Germany’s overwhelming Blitzkrieg. Following their defeats, both countries contained considerable sums of Partisan and guerilla forces, which provided a twofold "approval package": first, both countries became rehearsal grounds for systematized Partisan/guerilla warfare that the Wehrmacht would experience later in the Soviet Union; second, their resistance provided impetus for a formal policy of massive reprisal killings, which almost always targeted racial categories like Jews. In the grander scheme, in conjunction with methods of abnormal warfare practiced elsewhere, the Wehrmacht was successfully desensitized for both their war against the Soviet Union and their participation in the systematic liquidation of Untermenschen.

Yugoslavia: the Case of Serbia

Yugoslavia’s populations were both highly receptive and staunchly resistant. Croatia, for example, was headed by a collaborationist government, while Serbia and Macedonia contained significant amounts of resistance forces called Partisans. While examining each of these areas would be illuminating, Serbia provides the best case study as the bulk of substantive literature has been written on it and the anti-Partisan war was particularly gruesome there. Postwar statistics confirm that Serbia was the location of one of the most efficiently applied efforts of liquidation: in April 1941, "approximately 17,000 Jews lived in Serbia under German military rule. One year later, Serbia was ‘free of Jews.'"79 This came at the behest of General Ludwig von Schröder, the Wehrmacht commander in Serbia, who ordered that all Gypsies and Jews be identified, registered, and subjected to forced labor.80 Thus, the standardized persecution of Jews in occupied areas began with the occupation of Serbia, all the while supervised and many times directly implemented by the Wehrmacht. If anything was to prophesy the nature of warfare in Serbia, it was the codename for the initiative bombing of Belgrade marking the invasion of Yugoslavia: "Unternehmen Strafgericht," or "Operation Punishment."

The case of Serbia in 1941, Christopher Browning argues, is somewhat unique relative to other areas of German occupation. This is because he considers it a "minor theater not at the center of Hitler’s 'war of destruction' and quest for Lebensraum" which diminished the role of the SS. As a result, "military commanders there had greater latitude to act according to their own inclinations, attitudes, and values." Traditional Wehrmacht historiography would assert that this relative autonomy would lead to a more orderly and principled occupation, however it is the contradictory nature of the Wehrmacht’s behavior here that typifies the coalescence of military and Nazi attitudes. Several factors contributed to the Wehrmacht’s irregular warfare in Serbia, including the "Nazi political culture exulting in unfettered power, violence, and racial superiority," the exhortation of troops to be "‘tough’ and to act like true Herrenmenschen," and the denigration of Slavic populations, which when combined resulted in a "predilection for violence and atrocity."81 Field Marshal Wilhelm List, German occupation commander of the Balkans in 1941 and a "deeply religious non-Nazi," described Serbs at the Nuremberg trials as "far more passionate, hot blooded, and more cruel."82 This description, although partially rooted in historical prejudices, arose from the irregular, Partisan warfare that was waged in Serbia. Still, while their numbers and presence were considerable, the Wehrmacht’s response was astoundingly disproportionate, targeting Jews, Gypsies, and Serb civilians as either "Partisans" or victims for reprisal killings. Communists were eventually added to this list after Germany invaded the Soviet Union, having previously been exempted by the pact between the two countries.

![]()

![]() Figure 5 Execution squad of the Wehrmacht's Großdeutschland Regiment performs its task in Šabac.

Figure 5 Execution squad of the Wehrmacht's Großdeutschland Regiment performs its task in Šabac.

To be fair, or at least as fair as one can be in such an examination, the Partisan situation in Serbia was rather muddled, contributing to the confusion of the Wehrmacht. For that reason, it must be noted. In August 1954, the U.S. Department of the Army published a pamphlet titled "German Antiguerilla Operations in the Balkans (1941-1944)." The crux of their study of Yugoslavia is that the Partisan movement there was disorganized to the extent that a mini civil war was actually occurring between resistance forces. Involved were the "Chetniks" headed by Col. Draja Mihailovitch, the formal commander of the resistance forces in Yugoslavia, and the Partisans, headed by Tito. The former generally engaged in "restricted to small-scale actions and sabotage," while the latter were Communist irregulars who engaged in guerilla warfare. Complicating matters further, there were bands of guerilla fighters who operated under their own authority.83 Thus, Partisanship was erratic and rampant, impelling the Germans to simply combine all under the tag of Partisan. Nevertheless, this does not absolve the Wehrmacht of their decision to resultantly target civilians and Jews, as an informal policy of discriminate decimation predated those actions.

The Partisans did find success in thwarting a smooth Wehrmacht occupation. However, their virtue was also their vice, as the guerilla tactics enabled the Germans to justify massive reprisals or "atonement" executions of civilians. Initially, Wehrmacht leadership explicitly ascribed the SD-Einsatzgruppe the role of suppressing Partisan resistance – hostage shootings were the immediate result, targeting Jews, Gypsies, civilian Serbs, and eventually Communists. The Wehrmacht was responsible for burning villages following Partisan attacks and arresting "suspicious persons" that would be handed over to the Security Police. In effect, the Wehrmacht provided the Einsatzgruppe with their "hostage reservoir."84 Nevertheless, the Wehrmacht did engage in the execution of civilians. On April 22, 1941 in Panevo, for instance, eighteen civilians, including one woman, were hanged in a cemetery while fourteen more were shot along the cemetery wall by a Wehrmacht execution squad. Leaving their bodies hanging for several days as a deterrent, it was a reprisal for the death of one soldier and another who was seriously wounded.85 The relationship between the Wehrmacht and the SD units would soon change as the military apparatus saw an expansion of their role in the Partisan war, particularly when the Soviet Union was invaded on June 22, 1941.

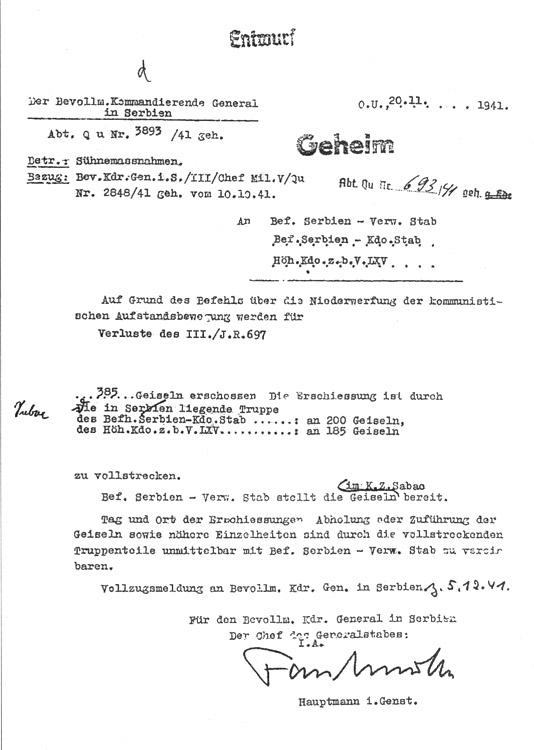

With Operation Barbarossa came a marked shift in the manner in which occupation and offensives were implemented. In Yugoslavia, orders were given for the radicalization of warfare, and in some cases, Wehrmacht leadership adamantly pressed for this. When Gen. Heinrich Danckelmann demanded that the OKW approve the addition of further SD attachments to Wehrmacht units, they denied his request, informing him that: "Due to turmoil and an increase in acts of sabotage, the Führer expects [Wehrmacht] troops to be used to restore peace and order through quick and decisive action." Thus, the Wehrmacht took up the struggle against the Partisans, forming mobile strike forces that were supplemented by members of police battalions and the SD. The scope of these groups’ tactical clearances was unrestrained, and their coalescence marked the disbandment of overtly delineated functions to cooperative efforts between the Wehrmacht and SS units – members of the Wehrmacht now began to familiarize themselves with SS techniques of liquidation. 86 Still, formalized, direct involvement by the Wehrmacht in the killings did not officially begin until General Franz Böhme was appointed Plenipotentiary Commanding General of Serbia in September 1941.

Not surprisingly, on the same day as Böhme’s appointment came the issuance of Keitel’s order on "combatting Communist insurrection in the occupied regions," which anticipated the execution of anywhere from fifty to one hundred Communists as a "reprisal for the life of a German soldier."87 Böhme was a hardline General, and his appointment spelled the doom of the enemy population. He quickly declared the entire population to be the enemy, having all men arrested and interned in prisons and concentration camps, women and children driven from their homes, villages burned, and livestock confiscated – all done in an effort to send a message to the Partisans of Serbia.88 He also took Keitel’s order to heart, eventually issuing orders that systematized the ratio of executions to victims of Partisan attacks at 100 to 1. Böhme’s first reprisal order came when 21 soldiers were killed by Partisans. Adhering to the 100 to 1 ratio, he issued the following order: "The Chief of Military Administration is requested to select 2,100 prisoners (primarily Jews and Gypsies) in the concentration camps Šabac and Belgrade." This was the first time that the Wehrmacht was ordered to carry out the executions of “hostages,” with the 342nd Division and Corps Intelligence Section 449 responsible in this particular case.89 Eventually, on October 10, 1941, much to the satisfaction of the SS, Böhme issued his comprehensive extermination order, targeting "all Communists, people suspected of being Communists, all Jews, [and] a given number of nationalist and democratically minded inhabitants…" These individuals were to be "seized as hostages in swift operations” and told that “hostages will be shot if German soldiers or ethnic Germans are attacked."90 The results of this order were catastrophic.

![]()

![]() Figure 6 "Hostage Execution" form for the execution of 385 hostages from the Šabac concentration camp.

Figure 6 "Hostage Execution" form for the execution of 385 hostages from the Šabac concentration camp.

Böhme appealed to historical reminiscences, informing all units that "You are to carry out your task in an area in which, in 1914, rivers of German blood flowed as the result of the duplicity of the Serbs, men and women. You are the avengers of these dead."91 Wehrmacht soldiers, for the most part, willingly responded to such justifications. In Oberleutnant Walther’s November 1 report, he noted that "Shooting Jews is simpler than shooting Gypsies. One has to admit that the Jews die stoically, standing quietly, while the Gypsies howl, scream…"92 Another Oberleutnant, Walter Liepe, casually recounts the executions of hundreds of Jews on different occasions in his field report, at one point stating that, "the units returned to their quarters well satisfied."93 In fact, the mass murder of these so-called "hostages" had become so commonplace by December that "Hostage Executions" forms were printed to hasten the process: to be written was the date, incident "atoned for," number executed, and unit who performed the execution.94

There are two notable massacres which demonstrate the magnitude of reprisal killings by the Wehrmacht in Serbia. First, the massacre in Kraljevo occurred on October 16, 1941. Partisan and Chetnik forces surrounded Wehrmacht units in the vital defensive point of Kraljevo, prompting them to round up hostages comprised of Communists, nationalists, democrats, and Jews on the 14th. On the 16th, members of the 749th and 737th Infantry Regiments and the 717th Infantry Division executed 1,736 men and 19 women. Gen. Böhme lauded these efforts in his October 20 order of the day, "I express my admiration to all officers, non-commissioned officers, and enlisted men who were engaged in these successful operations. Onward to new deeds! Böhme."95 These new deeds came in the second massacre occurring in Kragujevac. Here, more than 2,300 Serbs of all ages were executed to atone for 10 dead and 26 wounded Wehrmacht soldiers in the area. The execution occurred on October 20 after the Wehrmacht had dragged men and boys, including entire school classes with their teachers, into holding barracks. These executions were similarly praised, particularly the "aggressive spirit" and "initiative of the troops" that did not "tend to passivity."96

In Serbia, thus, we see the initial phases of Wehrmacht complicity in systematic executions of contrived enemies. Wolfram Wette argues that "In the Serbian theater of war the Wehrmacht not only created the political and logistical conditions for murdering Jews – as became the rule in the Soviet Union – but also planned their extermination itself and then proceeded to carry it out."97 Yet their targeting of Jews also expanded beyond males here, as the Wehrmacht assisted in the collection, imprisonment and gassing of women and children. They of course held to the absurd justification that Jews and Gypsies were "clearly informants for the rebels," and knowingly led women and children into mobile gas vans that were being employed by March 1942.98 However, the complexity of Wehrmacht complicity may not have become as radicalized in Serbia had not the invasion of the Soviet Union during Operation Barbarossa occurred.

Greece

In Greece, the anti-Partisan war similarly dictated the treatment of civilians. It resembled Yugoslavia much in the same way in that, because they were under the military administration of the Wehrmacht’s Commander Southeast, civilians felt the effects of terroristic warfare. In the Hamburg Institute’s examination of the Wehrmacht’s crimes, they contend that their executions "fanned the flames of national resistance," leading them to respond with more selective reprisals, targeting Jews, Roma and Sinti.99 One common practice in direct contravention of international law was the use of hostages (mostly Jews from the concentration camp at Haidari) as “human shields.” On the Salonika-Athens railway-line, for example, the first two cars of troop and supply trains were open-platform cars loaded with hostages. This would in theory discourage Partisans from attacking railway lines.100

![]()

![]() Figure 7 Officer in the 7th Parachute Division finishing off executed "Partisans" in Kondomari.

Figure 7 Officer in the 7th Parachute Division finishing off executed "Partisans" in Kondomari.

Reprisals further characterized the Wehrmacht’s invasion and occupation of Greece. When German paratroopers first invaded Crete in May 1941, the Cretan islanders assisted in the defense of the city. Crete was taken in late May, and a livid General Kurt Student, commander of the XI Air Corps, ordered "Revenge Operations" to be carried in response to their participation. His instructions were unambiguously distributed: "1) Shootings; 2) Forced Levies; 3) Burning down villages; 4) Extermination of the male population of the entire region."101 The following day on June 2, Greeks were executed in Kondomari, and the vengeance spread elsewhere, including Kandanos and Alikanos. Estimates place the total number of civilians shot in response to Crete at 2,000 (this number may be exaggerated however). Regardless, General Student and other Wehrmacht commanders in Greece dismissed their soldiers from the outset of all criminal culpability in the shootings of citizens as "reprisals."

By 1943, the complexity of the occupation of Greece had changed dramatically. Fearing an Allied invasion, coupled with an increase in Partisan attacks, the Wehrmacht’s treatment of civilians became increasingly brutal.102 In Kalavrita on December 10, 1943, the largest single massacre in Greece occurred in response to the capture and execution of a German company of about eighty in October. This reprisal resulted in the torching of 24 towns and villages, three monasteries, and 696 civilians shot. The request emanated from Generalmajor Karl von Le Suire of the 117th Jägerdivision, who ordered his men to "level" the villages which had supported the Partisans.103

On August 16, for instance, 317 Greeks from of all ages and both sexes were murdered in the town of Komeno. Committed by the 12th Company of the 98th Regiment of the elite First Mountain Division shortly before dawn, the massacre was carefully orchestrated, as the company of about 100 men encircled the town, firing a flare to alert assault squads to storm the houses. One of the ancillary troops later recalled, "So far as I could see from the tangled mass of humanity there were more women and children than men there."104 What is significant about this event is not only the scale of its inhumaneness, but the participants’ justifications several years later. All of the soldiers agreed that it was done as a reprisal, but glaring discrepancies existed as to who it revenged.105 The Komeno massacre is significant in this respect: for many Wehrmacht soldiers, reprisals killings did not harp on deep-seeded despondency for the loss of fellow combatants, but rather blind and impulsive hatred, likely rooted in xenophobic sentiments; crimes committed in the Soviet Union certainly support this. In other words, these soldiers could not recall who they avenged, but merely followed orders out of some sort of impulsive rage. In effect, this strips reprisals of any tactical credibility (which they arguably lack nonetheless), but instead makes them strictly criminal actions. Unfortunately, impulsive hatred became the catalyst for so many so-called Untermenschen losing their lives during measures of atonement, especially in the Soviet Union.

The Soviet Union: Terror Unleashed

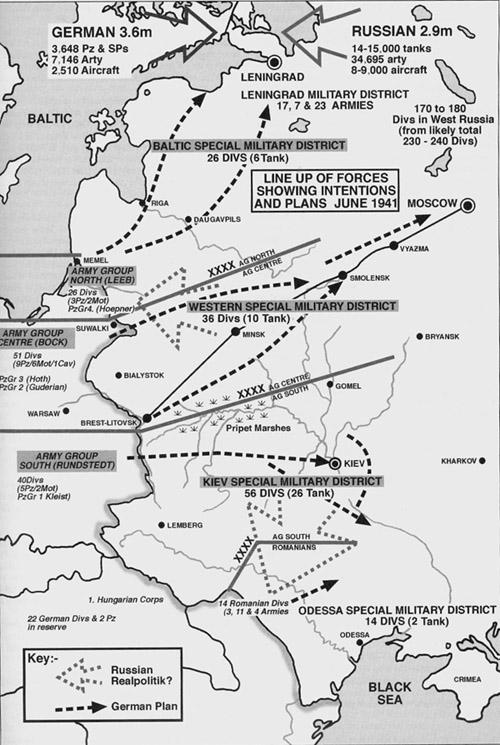

![]()

![]() Figure 8 Operation Barbarossa was intended to overwhelm with swift, decisive, and relentlessly brutal tactics.

Figure 8 Operation Barbarossa was intended to overwhelm with swift, decisive, and relentlessly brutal tactics.

That it was long Hitler’s intent to wage a war with the Soviet Union is of little question; such an assumption is only further supported by evidence dated December 18, 1940. Titled "Directives for Special Areas to Order #21" (Barbarossa), it specifically laid out the various areas of operation, the governing authorities, and Hitler’s incontrovertible primacy over the Wehrmacht. Occupied territory was divided between the North (Baltic countries), Center (Byelorussia), and the South (Ukraine). One particular paragraph ordered that the commanding officer in each of their territories was "the supreme representative of the Armed Forces in the respective areas and the bearer of the military sovereign rights. He has the tasks of a Territorial Commander and the rights of a supreme Army Commander or a Commanding General." Thus, they were given the following responsibilities:

"Close cooperation with the Commissioner of the Reich in order to support him in his political task… Exploitation of the country and scouring its economic values for use by German industry... Exploitation of the country for the supply of the troops according to the needs of the OKH… [and] Billeting for armed forces, police and organizations, and for IW’s inasmuch as they remain in the administrative areas."One last stipulation held that the commanding officer’s orders superseded all others, including civilian agencies and commissioners of the Reich.106 These orders are significant because they provided Wehrmacht commanders with orders that spelled the crimes to be committed by them. As it will later be evidenced, the Wehrmacht supported and engaged in numerous crimes against the Soviet population and POWs in accordance with their authority prescribed here. Thus, authority within these occupied territories rested predominately in the hands of the Wehrmacht high command, imputing them full accountability.