|

|

by Yale F. Edeiken

At West Point the cadets are told that amateurs discuss tactics, professionals discuss logistics. The same is true in litigation, especially civil litigation. Amateurs natter on about "burden of proof," professionals focus on the "theory of the case."

In the terms of modern civil litigation "burden of proof" has been reduced to a technical question which has little practical importance to the outcome of the trial. The main practical importance of issues relating to the burden of proof is in criminal litigation where the defense is often that the state has failed to meet its burden of proving its case beyond a reasonable doubt. In civil litigation, this is not a winning strategy. Civil litigation is won or lost on who can persuade the trier of fact - a jury or a judge - that his case is the stronger. Indeed having the burden of proof is often an advantage as it gives a plaintiff the first shot at the minds of the jury. This can be a distinct advantage in practice. The experts agree that the best way to meet the "burden of persuasion" necessary to win a case is to formulate a theory of the case and to plan trial strategy around it. Instead of doing this David Irving concentrated on the unusual burden of proof placed on a defendant by the vagaries of British libel and forgot entirely about his burden of persuasion.

David Irving's opening statement to the court, as are all opening statements, was a series of promises to the court about what he could prove. Irving stood in the well of the court and made promise after promise as what his evidence would be and what it would show. From beginning to end it was a series of distortions, exaggerations and fabrications that had the inevitable effect of destroying Irving's credibility even before he tried to establish it. The modern rules of discovery insure that there are very few surprises in a civil trial as to what the evidence will be. Irving and the defense knew what the evidence would be introduced in this case before it began. From Irving's patent misrepresentation in his opening statement that the Holocaust was not relevant to the proceeding, to his final claim of a world wide conspiracy to falsely besmirch his reputation, Irving's opening statement was a series of promises that Irving, the defense, and the court knew he could not keep. To make the hole he was digging for himself even deeper, Irving was so intent on his paranoid fantasies of Jewish conspiracies (which seems to be the facade that keeps Irving from admitting his own failures as a historian) that Irving even forgot what this trial was about. The statements that Prof. Lipstadt had made about him in Denying the Holocaust in 1993 were almost forgotten in the tedious debates about the meaning of German words.

For David Irving the most simple and most direct theory of the case was that Deborah Lipstadt made false and defamatory statements about him which had damaged his reputation as a historian. This was, in fact, the theory Irving presented in his Statement of Claim. His later assertions that this alleged defamation was the result of a broad Jewish conspiracy was not even mentioned in passing in that document. Had Irving stuck to this basic theory the evidence in his case would have revolved around the statements made by Lipstadt. Instead Irving decided to pursue a far broader theory of the case - he began to claim that the defamation was the result of a world-wide conspiracy to persecute him conducted by various Jewish organizations. And, as a result, Irving and his ability as a historian were the central issues rather than Lipstadt's statements.

Although he hinted at his approach in his Reply to the defense answer to his Statement of Claim, Irving's claim of a broad Jewish conspiracy was first explicitly introduced in the legal record with Irving's Witness Statement. In that document Irving made the claim that there was an international conspiracy to destroy him. The crucial allegations that set forth Irving's "conspiracy" are in a section entitled "The conspiracy to destroy and defame." It can best be described as a paranoid rant which had little, if any, relevance to the basic question of whether Irving was defamed in Denying the Holocaust and did nothing more than detract from that issue:

"25. In about 1992 I began to suspect that there was a concealed conspiracy to defame me abroad, and to destroy my reputation and thereby injure my professional career. It has become possible only in retrospect to piece together how these aims were achieved or partially achieved. Since this material is relevant to the issues before the court, I have introduced it in evidence.

"26. Disturbed by what was happening, I obtained access, by instructing firms of reputable solicitors in Canada, Germany, Australia, and elsewhere, and by proper use of legal instruments (e.g. in Canada, the Access to Information Act) to previously secret documents about me which astonished me. Sometimes they even revealed academics whom I had trusted and with whom I had co-operated as treacherous characters who simultaneously but secretly sought to achieve the suppression of my views, the failure of my books, the silencing of my lecture tours, my public humiliation, expulsion from countries, exclusion from archives, and even imprisonment.

"27. Although a best-selling, high-profile professional historian, I have been subjected to a campaign of boycotting, hounding, persecution and de facto punishment by organisations based in the U.K., Australia, and elsewhere overseas, designed to harass, vilify, threaten, assault, silence, and permanently commercially ruin me. I am aware of other historians who have similarly suffered. I noticed that the phrase 'Holocaust denier' came into the common currency of the published media. I was physically and violently attacked in the street and in a restaurant in 1992. My family and I have been subjected to an organised barrage of obscene, violent, and abusive telephone calls. The Board of Deputies of British Jews and its satellite and related organisations staged violent street demonstrations, for which they publicly took the credit, at my place of residence and at venues where I was to speak, which required heavy police reinforcements to protect.

"28. These opponents have furthered their aims by clandestine means, furnishing perjured statements about me to foreign governments and starting whispering campaigns against me - spreading for example the odious tidings that I had supplied the trigger mechanism used for the Oklahoma City bomb in 1995; they have applied violent and/or psychological pressure to my reputable publishers (like Macmillan Ltd in 1989 and again in 1991 and 1992) to violate fair contracts freely entered into, and they even forced them on one occasion (The Sunday Times, London in July 1992) to refuse to pay moneys owing to me under such a contract. Among their methods of intimidation, which bear a close comparison with the methods used by the Nazis in the 1930s, these organisations have started campaigns of book-burning and window-smashing against bookstores in the U.K., and they have blackmailed printers in Britain and Denmark, to my knowledge, to abandon production plans for books written by me.

"29. The Work Complained of, Denying the Holocaust, written and published by the Defendants, was the principal instrument deployed in the campaign to destroy me. The author, the Second Defendant, was financed and promoted by the same organisations as lay at the root of the international campaign, and funded with copies of the same smear materials that these organisations had concocted against me."

With this document, Irving's allegations that there was a long-standing conspiracy to fraudulently destroy his reputation as a historian and that Deborah Lipstadt had been a paid agent in a vindictive campaign against him became the real theme of the trial. This is reflected in both Irving's opening statement at trial and his closing argument. Even with this expanded theory of his case, however, Irving's first task was to convince the judge that Prof. Lipstadt's statements were false and defamatory. In his determined effort to prove this conspiracy, Irving forgot the basic issues of the litigation. Instead Irving decided to focus his opening statement on his reputation and the conspiracy to persecute him. It was a mistake that was to cost him dearly.

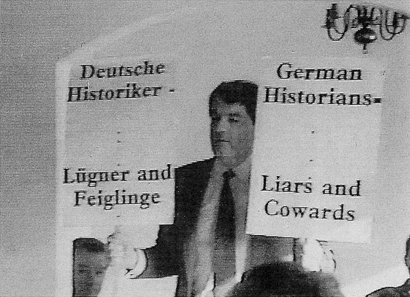

David Irving. Caption reads: "Revisionist meeting in

Hagenau, France." *

The purpose of an opening statement is not to argue the case to the judge or jury that will be deciding the facts. At the beginning of a trial they have not yet heard the evidence and, therefore, not yet ready to have the meaning of the evidence explained to them. The basic purpose, therefore, is to provide the trier of fact with an explanation of what the case is about and what the evidence will prove - it is the attorney's chance to both expound upon his theory of the case and, even more important, alert the trier of fact as to the most significant evidence that supports that theory.

Many experts consider the opening statement in a trial to be the most important function of an attorney. Studies have shown that over 70% of jurors form a firm opinion of the case after hearing the opening statements. It is important, therefore, to make an opening statement as concise and as factual as possible. It is not the time for passionate pleas, for the trier of fact - whether judge or jury - knows little of the case or the evidence and is not impressed by histrionic appeals. There are no greater mistakes in any opening statement than offending the common sense of the judge or jury or promising evidence that does not exist. Irving made both of those mistakes.